When you think of housing shortages, particularly affordable housing shortages, you likely think of San Francisco, New York City, maybe even Washington, D.C. You don’t think of Nashville, Tenn., or of Milkwaukee, Wisc. That is if you think about affordable housing shortages at all….

“This is a larger problem than you would think,” says Erika Poethig, institute fellow and director of urban policy initiatives for the Urban Institute. “Housing has not risen to the national debate.”

Sure, in the New York Democratic primary, voters pressured Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders to visit public housing in New York (did you know one in nine New Yorkers live in public housing?), but overall, says Poethig, “people are experiencing affordability challenges more than we realize.”

That was the subject of Matthew Desmond’s recently published Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (Crown, 2016). In the book, Desmond, a Harvard University professor and co-director of the Justice and Poverty Project, follows the lives of Milwaukee’s overlooked urban poor — those who may spend as much as 96% of their income on housing and who often move from place to place, with kids, in a relentless aura of poverty, housing insecurity and danger.

Yet despite the lack of public debate, 58% of Americans polled in a 2014 survey supported by the MacArthur Foundation feel affordable renting housing is difficult to find. And according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, only 28 in every 100 extremely low-income renter households in 2013 felt they were able to find safe and affordable homes.

In Nashville, a decidedly “big little city,” growth post-Recession has been meteoric. “Over 80 people move to Nashville daily,” said Adriane Bond Harris, senior advisor, affordable housing, with the city’s Office of Economic Opportunity and Empowerment (a recent creation of newly elected Mayor Megan Berry). “We’re the ‘it’ city,” says Harris, “but we want to be the ‘it’ city for everyone.”

Easier said than done.

Nashville is facing the same problems so many metro areas around the country are facing—there’s job growth, there are a lot of new people moving in, housing costs have gone up due to the inability of supply to meet demand and wages have remained stagnant. And the closer citizens are to the bottom of the wage ladder, the more stagnant earnings are.

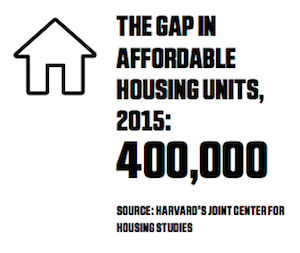

According to Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, the supply gap in 2015 was 400,000 units. Of course, that leads to price inflation on rental rates for existing units as well as driving developers to build. But today’s construction isn’t necessarily providing for all of tomorrow’s renters.

THE PROBLEM OF PROFITABILITY

Harris acknowledges that developers see Nashville as a hot market for new multifamily construction, but the problem is affordable housing just isn’t profitable to build without government subsidies and support. “The market is moving faster than the government,” Harris noted.

That doesn’t mean the city isn’t trying. Nashville’s Metro Council recently earmarked $10 million for the Barnes Affordable Housing Fund to go toward construction of affordable housing units. A year ago, that fund received only $2 million.

Nashville has also launched a campaign to use vacant metro properties owned by the city as constructions sites for affordable multifamily units. Right now the city is partnering with a private developer to build workforce housing on two city-owned acres at the 12th and Wedgewood intersection. The project will feature 138 units leasing for 60% to 120% of local rental rates.

The city is also looking to pass an “inclusionary” zoning law that would provide tax incentives and subsidies to developers who voluntarily include affordable housing units in new construction. The subsidy could offer builders up to $20,000 per unit. However, the proposed program would be voluntary if enacted.

The city is also looking to pass an “inclusionary” zoning law that would provide tax incentives and subsidies to developers who voluntarily include affordable housing units in new construction. The subsidy could offer builders up to $20,000 per unit. However, the proposed program would be voluntary if enacted.

The problem, according to Poethig, is that there just aren’t enough government subsidies out there to allow for enough construction of affordable housing or rental assistance to families in need. She points out that only one in four Americans who are eligible for federal rental assistance actually receives it.

“These are appropriated resources,” Poethig explained, “and Congress is only able to distribute so much.” On top of that, the assistance is not evenly distributed across the country.

STAGNANT WAGES, RISING RENTS

Housing experts agree that as metro areas look at how to address affordability, they should consider the issues outside the silo of housing alone. “It’s not just about housing,” said Harris. “It’s also about access to employment and transit.”

Carol Galante, who served as Federal Housing Administration (FHA) commissioner from 2011 through 2014, and is now faculty director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California-Berkeley, doesn’t believe rental rates are a problem as much as income security is.

“There is a change in the economy toward more service occupations that pay lower wages,” Poethig said. “Globalization puts more pressure on wages.”

An increasing number of Americans lack access to full-time jobs with benefits and are cobbling together two or three part-time jobs to try and make ends meet. Meanwhile, part-time work is also less secure.

And while they may only spend the recommended 30% of income on housing, as Poethig points out, “Thirty percent doesn’t go a long way when your income is very, very low.” But that’s not the worst of it.

According to HUD’s 2015 Worst Case Housing Needs report to Congress, as many as 10 million very-low-income American households pay more than half their income to housing and utility costs.

Demand is an exacerbating factor right alongside rising rental rates. Nashville, for example, offers a property tax relief program to seniors, veterans, and citizens with disabilities to reduce pressure on their incomes so they can continue to afford the residences in which they live.

Where are affordable housing pressures worst? New York and San Francisco, of course, but also Seattle, much of the South as well as the Southwest. “These areas are growing rapidly and have extremely low-income families,” Poethig said.

Galante says the issue goes even deeper, however.

“I think it’s a twofold problem,” she said. “In job-rich economies and tech job cities like Seattle, D.C., San Francisco, and Portland, there’s a huge surge in demand because of employees relocating.”

Millennials often want to live in an urban environment, putting “a huge pressure on the rental housing stock at a time when those communities are doing all they can to bring supply online.”

Galante posits, “That’s the biggest problem. It’s not just people at the lowest end of the spectrum who face housing shortages.”

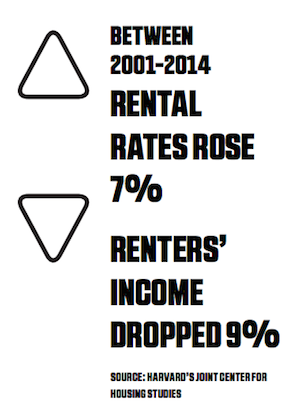

But they are facing the biggest squeeze. When the Great Recession turned millions of former homeowners into renters, it drove up rental rates, which rose nationwide by 7% between 2001 and 2014, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Meanwhile, renters’ income dropped by 9%.

By 2014, one in six American households was paying more than 30% of their income for housing, and today, more than 10 million pay more than half. The center further reported that, in 2014, only 30% of those housing insecure renters had full-time jobs.

WHAT ARE THE SOLUTIONS?

Despite the fact that it’s an election year, there has been little attention given to affordable housing in the public forum. And, as Poethig has noted, the government can only do so much anyway.

Among the solutions the Urban Institute has explored is leveraging public land. Nashville is giving that serious consideration, as is New York.

And in June, HUD announced a new policy, piloted in Dallas, that would increase the worth of rental vouchers to fair market value down to the ZIP code level, enabling families to obtain housing in high-opportunity areas. That way, in addition to affordable housing, they’d also have easier access to economic mobility.

HUD Secretary Julian Castro said of the new measure, “We propose to use a tested new approach that would offer these households greater choice to move into higher opportunity neighborhoods with better housing, better schools, and higher paying jobs.”

The new program will impact 31 metro areas. Castro said a Harvard University study recently concluded that when the children of low-income families move into higher opportunity neighborhoods, they are more likely to pursue post-secondary education and obtain higher paying employment as adults, providing promise for ending the cycle of poverty.

The new program will impact 31 metro areas. Castro said a Harvard University study recently concluded that when the children of low-income families move into higher opportunity neighborhoods, they are more likely to pursue post-secondary education and obtain higher paying employment as adults, providing promise for ending the cycle of poverty.

In California, the governor’s office is working on a proposal patterned after Massachusetts’ Comprehensive Permit Act: Chapter 40B that, broadly speaking, requires developers to include affordable housing stock in development plans with the goal that at least 10% of housing in every community be affordable for low- to moderate-income households.

The Massachusetts legislature also recently introduced an add-on to that law that would require communities to designate a certain amount of land for multifamily housing.

Among the largest U.S. counties, Suffolk County, which encompasses Boston, comes closest to meeting the housing needs of its extremely low-income households. But even so, Suffolk meets just over 50% of that population’s housing needs.

Meanwhile, the Dallas-Ft. Worth area suffers from the largest housing gap, providing only eight safe and affordable housing units per 100 extremely low-income renters.

And most metro areas have fewer affordable housing units available today than they did in 2000, according to the Urban Institute’s The Housing Affordability and Affordability Gap for Extremely Low-Income Renters (2013). Only the Boston area, Los Angeles, and Miami counties have increased availability of affordable housing since 2000.

Local and state governments have to step up to the plate to help fill in the gaps left by inadequate federal funding for affordable housing. Galante noted the cost of building today is “out of control.” A big part of that cost is eaten up by meeting local building requirements (which are especially stiff in Galante’s home area of the San Francisco Bay) as well as how long it takes for local governments to approve new development.

The Terner Center has been lobbying for scaling up much faster off-site modular construction in communities where there are major supply gaps. “This would help get construction costs under control,” Galante said. “The problem is getting governments to accept it.”

That, she said, is where private sector innovation needs to pick up the slack. The problem, she added, is getting developers, engineers, architects, builders, and manufacturers on board with modular construction.

“Architects are used to being able to make changes throughout the construction process, but for off-site construction, you have to make decisions that aren’t going to change six months later.”

At the Terner Center, Galante and her colleagues have developed a Housing Development Dashboard tool that allows communities to assess their housing markets, economies, and land use measures to determine where their housing pain points are.

“Local, state, and regional action is very important,” says Galante. “San Francisco just passed a bond measure to get more money for affordable housing. The federal government can’t be the sole answer, but the federal government does set the context, the standards for lending, and the tax code.”