A storm is coming, and this one has nothing to do with home prices, underwater borrowers, cash-only investors driving real estate purchases, or a massive set of borrower defaults.

It has to do with mortgage volume, and while many in the industry know that times are tougher right now than they were a year ago, few seem to expect those tough times to continue unabated for the foreseeable future.

But what if the mortgage market we are seeing today is, in fact, the new normal for the next decade (or longer)?

There are five good reasons to think this might actually be the case.

INTEREST RATES

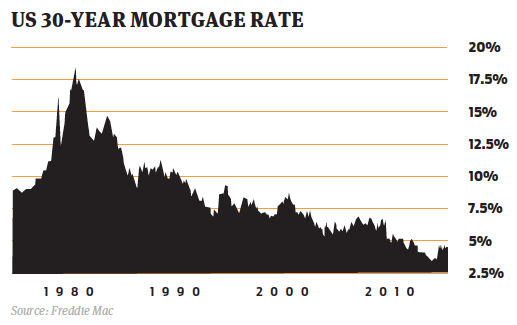

The average rate for a 30-year conforming mortgage stood at 4.41% for the week ended April 3, 2014, according to Freddie Mac data. And rates have largely hovered in the mid-4% range since June of last year — that’s the good news. Rates remain historically low.

But while rates remain low by historical standards, it’s far more important to recognize that rates are not relatively low.

In April of 2012, average mortgage rates fell well below 4% — thanks mostly to extraordinary market intervention by the Federal Reserve — and then stayed there until jumping up into their current range in June 2013. That’s 12 months of mortgage rates that were at absurdly low levels, and even today’s historically low rates end up looking relatively high in comparison.

More importantly, it’s not likely that we’ll see rates dip back below 4% any time soon unless the wheels come completely off the economy. (And if that happens, we’ll have much larger concerns than simply what’s going on with mortgages.)

The reason? The Federal Reserve has continued to peel back its support of the U.S. mortgage market, tapering mortgage bond purchases and effectively driving up mortgage rates ever so slowly in a bid to prevent the bond market from blowing up.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen has indicated that the Fed will continue to taper throughout 2014, suggesting that rates — if anything — will at best continue to tread water for some time. Eventually, they’ll rise further when the Fed does begin raising its benchmark Federal funds rate at some point in the future.

That could be in 2015, 2016 or even 2017, depending on whom you ask. But the point is this: mortgage rates aren’t likely to trend downward again anytime soon.

This is a massive change for anyone in mortgage markets, and here’s why: taking a long-term view at U.S. mortgages, the U.S. has enjoyed more than three decades of generally declining mortgage rates overall. From roughly 1985 forward to June 2013, average U.S. mortgage rates had been on a declining slope.

This is a massive change for anyone in mortgage markets, and here’s why: taking a long-term view at U.S. mortgages, the U.S. has enjoyed more than three decades of generally declining mortgage rates overall. From roughly 1985 forward to June 2013, average U.S. mortgage rates had been on a declining slope.

But what about now, and in the years to come?

At best, rates stay where they are; long-term, it’s a foregone conclusion that rates go up. Which means that for the first time in 30 some-odd years, the mortgage banking industry is going to face an environment where the long-term rate trend is upward, not downward.

This shift in a key secular trend will have broad impact on the mortgage industry. Few members of the modern mortgage banking profession were part of the industry’s last rising rate trend during the late 1970s to mid 1980s.

Those that were would tell you that it wasn’t the best of times for mortgage professionals.

The verdict: The mini-refi boom observed from 2010 to late 2013 is now largely relegated to history, while a secular trend shift toward rising rates means refi activity should remain muted for some time to come. That leaves the U.S. mortgage market largely dependent on purchase money for new forward volume.

RATE LOCKED BORROWERS

Nearly 22 million borrowers — or roughly half the market of all outstanding mortgages — refinanced their mortgage during the most recent cycle of low rates, according to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data. And as we discussed in last month’s column, recent research from DePaul University suggests that this group of borrowers isn’t likely to move from their current position anytime soon thanks to rising rates.

The good news, relatively speaking, is that half the market did not refinance — due to financial condition or their home being underwater, or some other factor — and with rates still historically low and home prices still rising at a decent clip, there is a chance this group might yet avail themselves of a refinanced mortgage. (Or serve as a move-up buyer driving purchase mortgage demand.)

The bad news is that the 22 million who did refinance are now rate-locked into their existing mortgage and unlikely to move elsewhere; research from DePaul University suggests these borrowers have effectively opted out of placing themselves into a “move-up buyer” category.

Move-up buyers — those who sell their existing home to buy a different, usually more expensive, home — represent as much as 40% or more of the purchase money market for mortgages historically, according to data from the Mortgage Bankers Association. With half of the viable market for move-up buyers now locked into low, low mortgage rates, it seems clear that at least some of the demand we would typically find from move-up buyers will spend this next cycle on the sidelines.

Just how much remains to be seen, and is a function of where mortgage rates go in both the near and long-term.

The verdict: Purchase mortgage demand from would-be move-up buyers will be weaker than in previous cycles due to the “rate lock-in” effect. Roughly half of the existing mortgage market is susceptible to this effect in varying degrees.

STAGNANT HOUSEHOLD INCOME

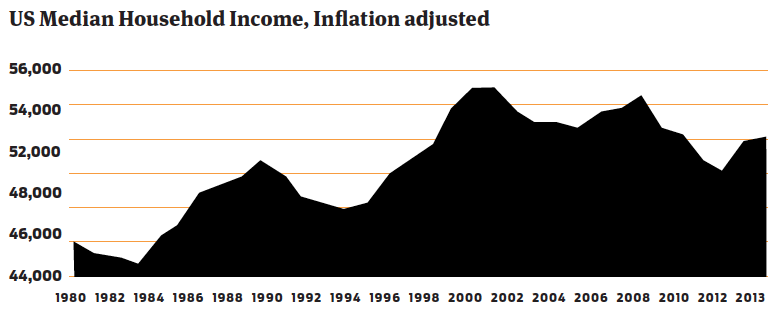

Beyond move-up buyers, purchase money demand for mortgages comes from first-time buyers. And in this market, income growth is everything — as new households form, household income has to be sufficient to support a mortgage.

The ugly truth? Adjusted for inflation, household income during 2012 (the most recent year data is available) was roughly equal to what households made in 1997. That’s over a decade of stagnant household income — meaning no growth.

The ugly truth? Adjusted for inflation, household income during 2012 (the most recent year data is available) was roughly equal to what households made in 1997. That’s over a decade of stagnant household income — meaning no growth.

Without income growth, it’s difficult for households to save the money they need to obtain a mortgage.

And it gets tougher. Beyond household income growth, the Millennial generation — those born after 1981 — thus far isn’t bothering to form separate households to begin with. From 2007 to 2010, an average of 550,000 households formed each year in the U.S., according to Census Bureau data; that’s the lowest level since records began to be kept after World War II.

As a result, in 2012, 45% of 18- to 30-year olds lived with older family members, a number that was 35% in 1980.

So traditional first-time buyers aren’t forming households at the rate of previous generations, and those who do are finding themselves having to fight against a climate of stagnant earnings — further limiting their ability to obtain a mortgage.

The verdict: First-time buyers will remain constrained in the near-term as the lingering effects of the Great Recession suppress household formation, and a tepid economic recovery drives stagnant household income levels. When combined with lagging demand from move-up buyers, this means that demand for purchase-money mortgages is likely to fall short of most expectations over time. Millennials are coming of age in a job market where 44 percent of recent graduates work positions that don't require a college degree, and where they and many of their peers are saddled with record levels of student loan debt. The Great Recession has effectively led to the Great Delay.

LACK OF CREDIT AVAILABILITY

Beyond factors likely to drag on outright mortgage demand, tight underwriting criteria and lack of available product options also mean that those borrowers who might otherwise be in the market to obtain a new or refinanced mortgage won’t be able to.

More than 80% of banks say they now expect new mortgage regulations to reduce mortgage credit availability, according to the American Bankers Association’s 21st annual real estate lending survey released in early April.

Further, a study by compliance specialist ComplianceEase in late 2013 found, for example, that of loans underwritten that year, one in five loans would not qualify under the new Qualified Mortgage standards. And with many lenders hemming their lending activity nearly exclusively to QM standards, that’s a lot of loan volume that could be lopped off the market in years to come.

The days of “liar loans,” “teaser rates” and “no money down” mortgages are gone, and that’s a good thing. But sticking to conservative lending standards isn’t going to help juice demand for new mortgages from borrowers who may be good credit risks, yet can’t access financing for their American Dream.

The verdict: The mortgage market will eventually bifurcate into traditional and non-traditional mortgage lenders who will do non-QM lending — and do it well. But this adjustment process will take time, and in the interim year or so expect mortgage credit to put a cap on mortgage origination activity.

POLITICAL INFIGHTING AND MEDDLING

Fannie and Freddie. The FHA. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The Federal Housing Finance Agency. The government’s role in U.S. mortgage markets has never loomed larger — and, in many cases, more contentiously than it does right now.

Politicians have figured out that the politics of housing are the same politics that help them get — and stay — elected. Which means the industry should expect more, not less, interference from government interests in the years ahead. And the mortgage industry is now at a distinct disadvantage to numerous special interest consumer groups that have set their sights on the mortgage industry in the wake of the financial crisis.

And regardless of political stripe, there is one truism in all politics: industries that are highly regulated by government tend not to grow as fast as those less regulated. That’s the road ahead for the U.S. mortgage industry, which was already heavily regulated before the crisis.

Now? Health care markets in the wake of ObamaCare almost look laissez faire, in comparison. The biggest growth business in mortgages isn’t in lending itself any more — but instead in managing the compliance and risk inherent in the lending process.

Worse than over-regulation, Capitol Hill is actively considering abolishing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac altogether — the only part of a functioning capital markets system for U.S. mortgages that we have left. While the GSEs certainly have their flaws, abolishing them would leave mortgage investment markets with no other viable alternative funding mechanism that can scale.

The verdict: Expect the politics of housing to only become more convoluted, complicated and contentious in the years to come — affecting the industry’s ability to effectively meet market demand for mortgage financing, while risk management and compliance services continue to grow in importance.

A PICTURE FOR THE LONGER HAUL

Is it any wonder that Bank of America Merrill Lynch found mortgage bond issuance in March 2013 the second lowest in over a decade?

Is it an anomaly that Black Knight Financial Services reported mortgage originations falling to their lowest level in over 14 years in February?

Putting the above five factors together, a picture of the future of mortgage lending emerges: a dwindling refinancing business, married with lackluster move-up buyers and a generation of would-be first-time buyers that has yet to get off the ground.

Mix in tight underwriting standards and strong government meddling, and you get the recipe for a mortgage market that on the whole doesn’t really begin to see strong growth for some time to come.

In other words, it’s time to put away the rose-colored glasses and face the new reality of mortgage banking in the United States: still a trillion-dollar industry, yes, but not a $2-trillion growth industry — and an industry that will be limited in its ability to contribute to economic.growth during this recovery cycle, as a result.