Since July 2008, the U.S. government has disbursed more than $6 billion in grants to rehabilitate vacant foreclosures. But now, more than three years later, communities are turning to and sometimes forcing private banks to foot the bill under an ongoing plague of blight. According to the Census data, the vacancy rate on residences stood at 2.4%, a full percentage point above the pre-crisis levels. A recent Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland study found that if a borrower abandoned the property while in the foreclosure process, home sales within 500 feet dropped 7.1%. Will millions of foreclosures still on the way in the years to come, the need to keep maintain these properties is growing increasingly desperate. “There is a tremendous need in the purchase rehab market,” said Joe Ott, a senior policy analyst at the Cleveland Fed at the Wolters Kluwer CRA & Fair Lending Colloquium in Baltimore Tuesday. “Banks can actively participate, and I see a lot of capacity on the bank side to handle a lot of the property issues.” Many, like Ott, say they’re not doing enough. One real estate investor, who asked not to be named, told HousingWire this week that banks and the government-sponsored enterprises are unwilling to finance her REO purchases and then reject her cash bids routinely even though she is forced to undercut the value of the home because it has sat vacant for sometimes years. “As the houses sit vacant, closed up, unheated, and without air conditioning, the houses are deteriorating. Some of them need $40,000 to $60,000 worth of work, so of course I need to subtract that from what I feel the house is would be worth in this market once it is fixed up,” she said. Local governments are beginning to crack down. A recently proposed ordinance in Las Vegas – which has led the nation in the highest foreclosure rate for years now – would force servicers to pay a $1,000 fine or even face jail time for failing upkeep these properties. A city in Illinois will begin to seize properties that have been left vacant for an extended period of time. Since 2008, Ott said, Community Reinvestment Act loans have been halved due to the crisis. Regulators routinely screen banks for the amount of loans being given to restore neighborhoods and finance new developments. Many smaller institutions have actually found some margin on the famously difficult rehab loans to investors, even the 203(k) program, which the government discontinued for investors. “With an aging housing stock, there is a need for credit on the ground for purchase rehab lending,” Ott said. “We all know 203(k) is a pain to work with, but the need is there. I will say that some, mainly smaller institutions have adopted very robust purchase rehab products, and the margin has been fine. It can be done in a safe and sound manner.” The $6 billion from the Department of Housing and Urban Development‘s Neighborhood Stabilization Program has gone out to nonprofit organizations through two rounds of grants. There is still opportunity for private banks to invest with those organizations for what Ott called “low hanging fruit” for banks looking to boost CRA compliance. But private banks will need to take more of rehabilitation load as government funds dry up. No new money will be on the way from a Congress looking to cut spending. House Republicans already approved a bill to defund the second round of NSP. The program survived only when the Senate decided not to take up the measure. “The capacity has been placid on the government side because of cut backs,” Ott said. “You have banks that are actively seeking out ways to help out. I see a perfect matchup there.” Write to Jon Prior. Follow him on Twitter @JonAPrior.

Three years and $6B later, efforts to stabilize neighborhoods still struggle

Most Popular Articles

Latest Articles

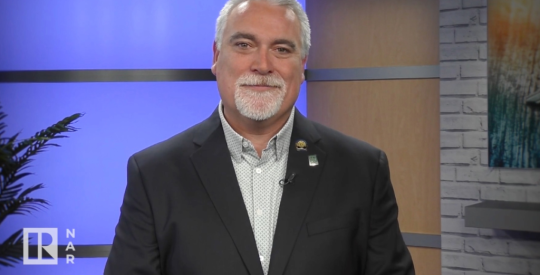

Kevin Sears pulls back the curtain on NAR’s commission lawsuit settlement

NAR’s president took to the stage at The Gathering just hours after the court granted preliminary approval of the commission lawsuit settlement agreement